Traditional tar (oil) is still very much alive!

History

I am not new to the product or production methods of (pine) tar and tar oil, but spending a week at the Nordic Tar Oil Seminar in Mariehamn, Åland ( Finland) showed me how much I still have to discover about this incredible product.

Pine and birch tar are the mother of all wood treatments and their use goes back to palaeolithic times. Birch tar is found more in Eastern Europe and Russia, whereas pine tar is the dominant version in most of the rest of Europe. Paul Kozowyk’s study has found that Neanderthals used pine and birch bark tar as a glue more than 100,000 years before Homo sapiens used tree resin in Africa.

This gradually moved to it being used as a wood treatment to repel water on boats and most likely to that of buildings.

As usual, the use of particular materials is based on local availability. Pine forest used to cover most of northern and central Europe, so pine tar is more prevalent in these areas. Birch tar is derived from the bark of birch trees, where the resin present in the bark is collected when the bark is being burnt, pine resin is derived from the burning of pine tree (Pinus Silvestris) roots. Even though derived from different timber and in a different process, they have very similar properties.

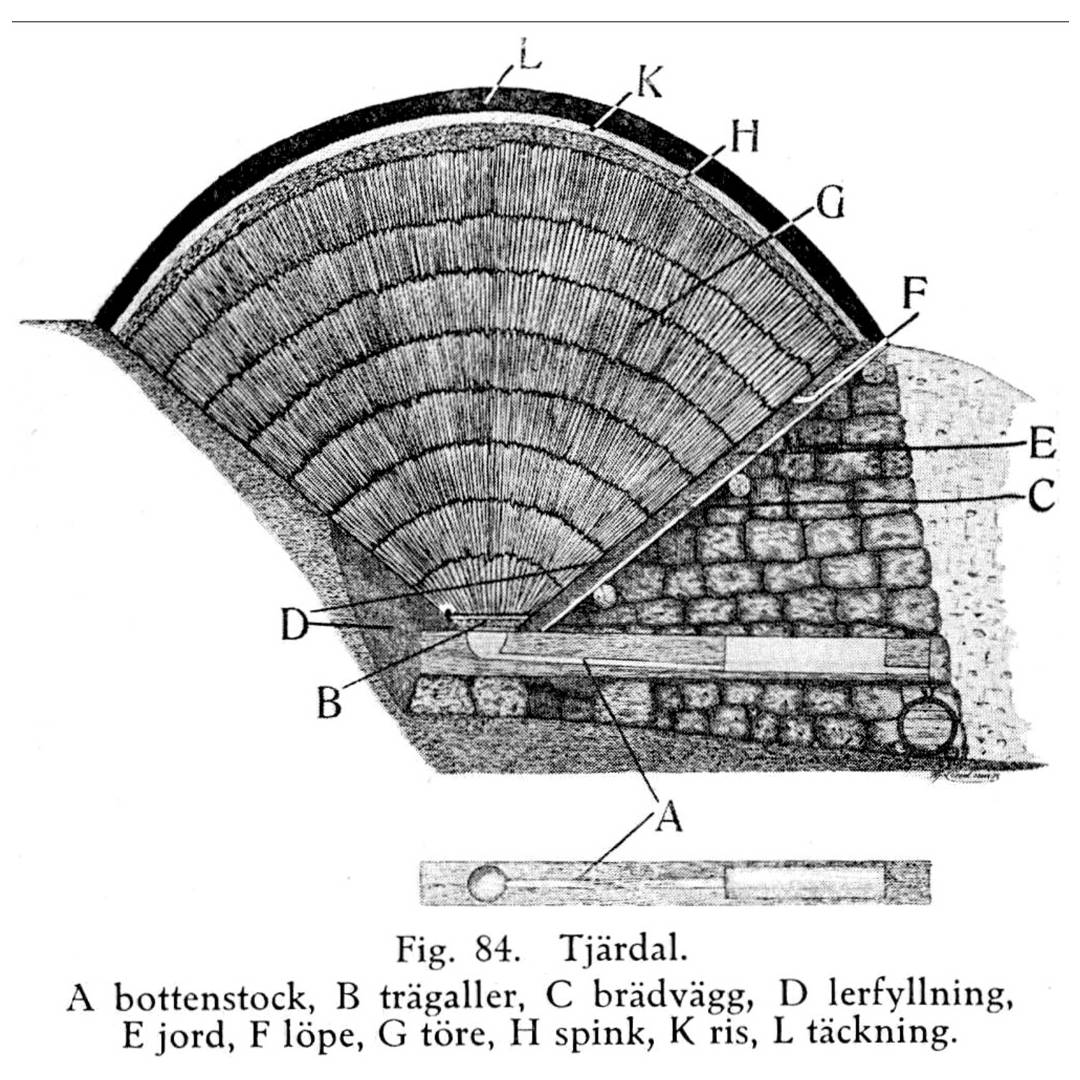

The National Trust of Norway last year carried out one of the biggest traditional pine tar productions in recent times, producing 10,000L in one batch.

Just like linseed paint, linseed oil and other traditional products and methods largely disappeared off the radar during the second World War and never really returned. Only the maritime industry kept using tar and linseed oil on a regular basis, in particular on timber boats and rope. Nowadays, it is still used in the marine industry, but mostly relegated to restoration work or timber, hand-built boats, like the ones at the Sjökvarteret, Åland’s craft centre for boat building.

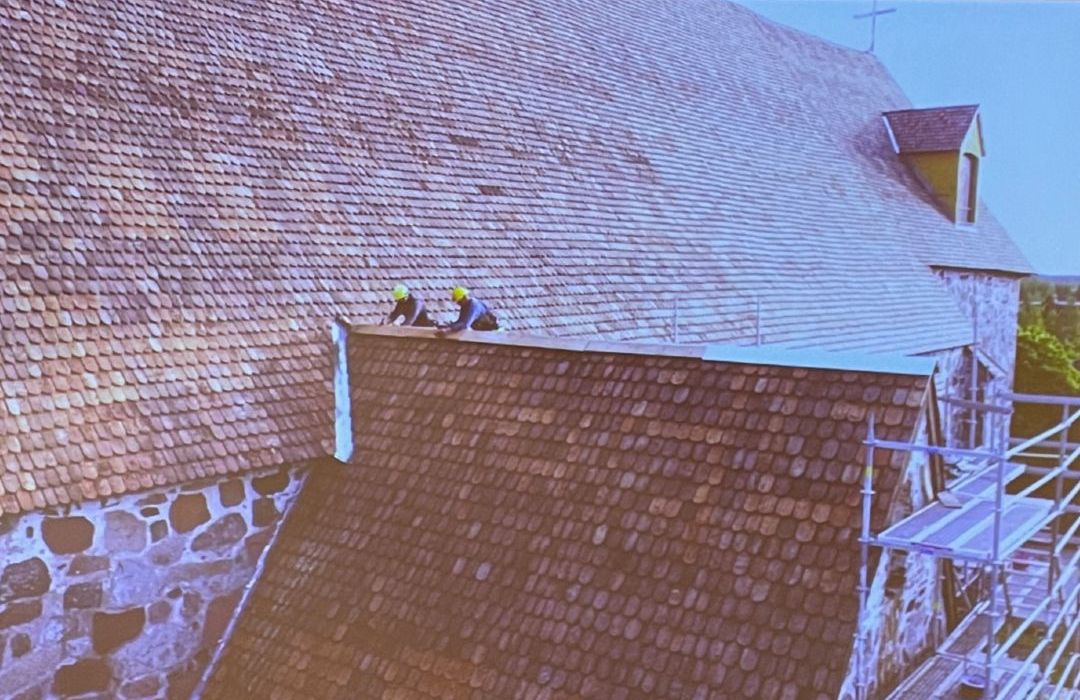

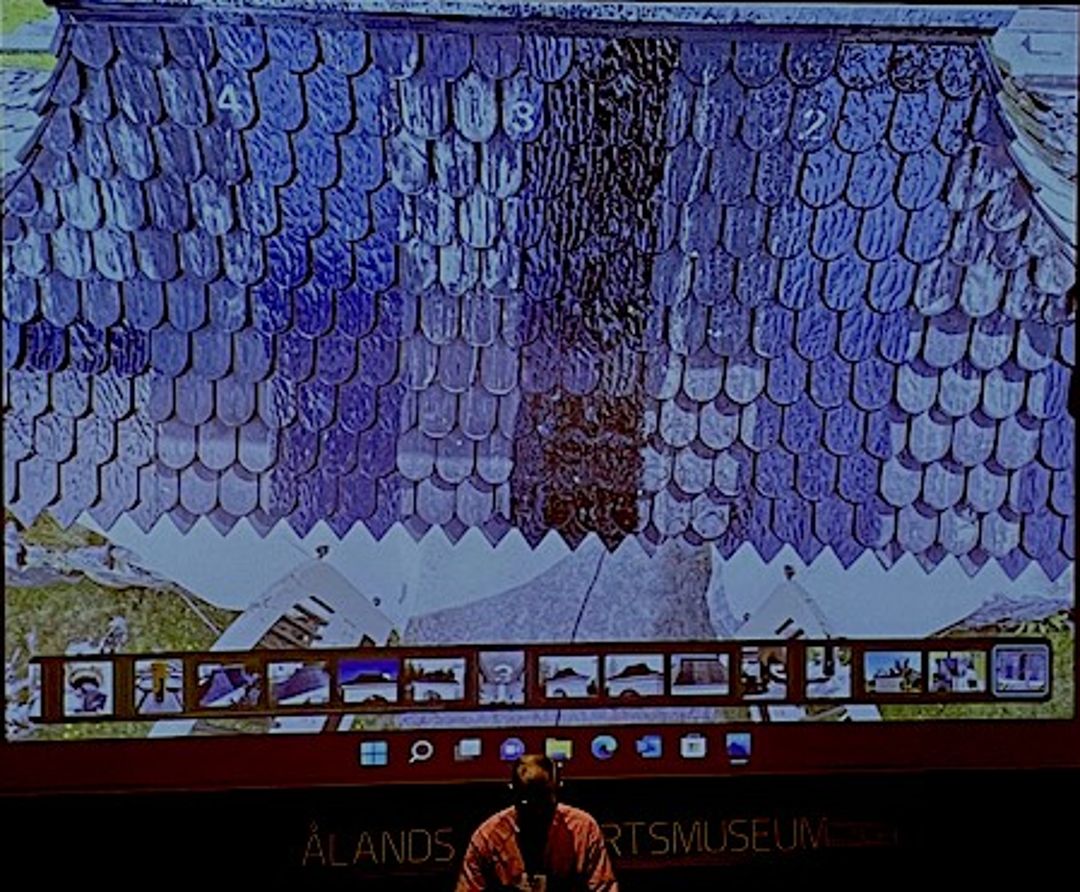

The best examples of applications of tar on historic buildings come from the ecclesiastical world. Not only is it the primary method of treatment for the Stave Churches in Norway and Sweden, it is also used on timber shingle roofs. The roof on Nykarleby church is a very good example, but it also shows the scale of the task in hand.

Testing

Egebnerg’s seminal research and thesis (Egenberg, I.M., Tarring Maintenance of Norwegian Medieval Stave Churches. (Göteborg Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, 2003), has shown how well tar works, and recent trial and research projects like this one lead by Daniel Wikstrom, property manager at Pedersörenejden’s Church Community, confirms the efficacy of tar oil, as long as it gets reapplied regularly. Once every 1-2 years for the first 5-6 years, then once every 2-3 years, depending on the elevation and exposure to UV light.

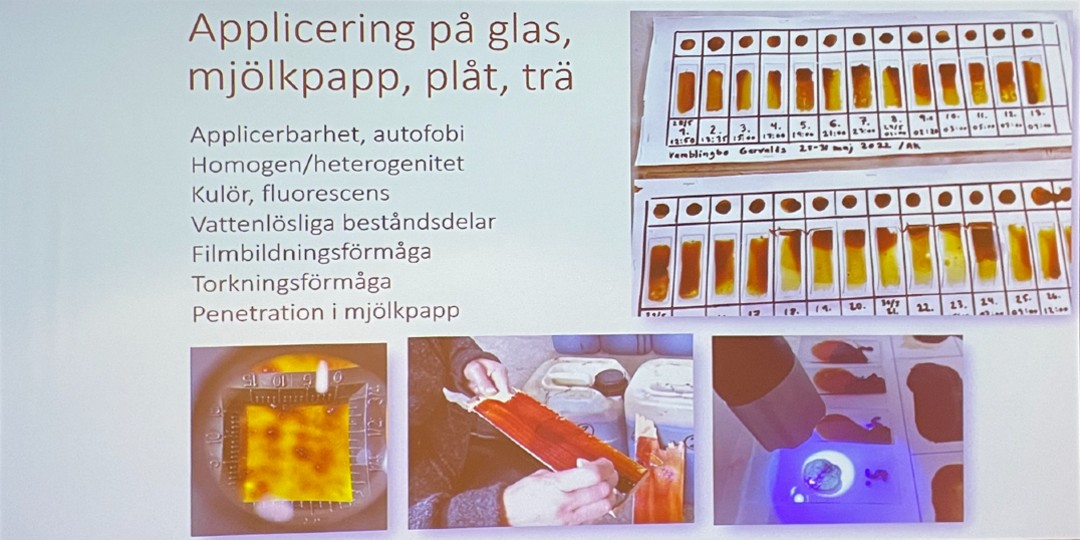

Arja Källbom and Linda Lindblad (University of Gothenburg for Svenska Kyrken) are extending Egeberg’s research by adding grading of tar oil. Because a kiln burn typically lasts between 9 and 13 hours, the tar coming out can vary quite significantly between the beginning, middle and end production. Therefore, not only is there a need to have more chemical analysis including rheology to ascertain viscosity and viscoelasticity (and don’t forget thixotropy, drying time, molecular weight distribution, stability, and gel point, but also sensory impressions. In case of the latter, think of smell, feel and colour).

The Present and Future

All trials and test projects show that kiln burnt tar is extremely effective at protecting and preserving timber in buildings and on boats. Even though the ingredients and production method are completely natural, the production of tar has been highly regulated by EU regulations due to the burning of tree matter. The Nordic Tar Network, under guidance of Ilkka Pollari, has managed to secure production rights for now, but the question remains how long this will be in place. It is not inconceivable that traditional pine tar production in kilns will be banned, with only retort options left. This may not be detrimental to the industry but actually provide an extra impulse in making the manufacturing method more environmentally friendly. Very interesting developments are already taking place in this area and I have one of the very first samples of tar produced as a by-product of biomass production (lead by Kim Lehiö). There is still quite a bit of headway to make before this product can be offered to the market, but the first signs are looking very positive. I look forward to seeing the chemical profile comparison done by Paul Kozowyk.

Unfortunately, the very labour-intense production of kiln-burnt tar is too expensive to be used on a relatively large scale. Add to that the limited production capacity, and you can see we need an alternative production method to be keep maintaining the buildings we love. In Norway alone, traditional production only produces about 1/10th of the demand. This discrepancy becomes only bigger in Sweden and Finland.

However, even though there are still some gaps to be filled in, it is safe to say that this highly valuable cultural and historic skill has been saved for the future and is being documented properly for posterity. Now, it is essential to find a production method which allows production on a commercial scale so the historic boats, churches and barns can be saved for the future!